Operation Blue Moon

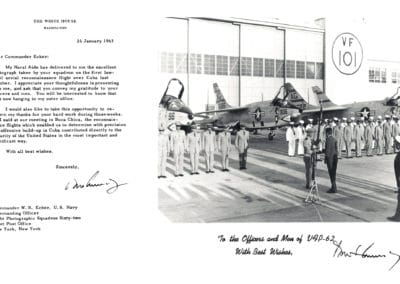

On October 23, 1962, a U.S. Navy commander named William B. Ecker took off from Key West at midday in an RF-8 Crusader jet equipped with five reconnaissance cameras. Accompanied by a wingman, Lt. Bruce Wilhelmy, he headed toward a mountainous region of western Cuba where Soviet troops were building a facility for medium-range missiles aimed directly at the United States. A U-2 spy plane, flying as high as 70,000 feet, had already taken grainy photographs that enabled experts to find the telltale presence of Soviet missiles on the island. But if President John F. Kennedy was going to make the case that the weapons were a menace to the entire world, he would need better pictures.

Swooping over the target at a mere 1,000 feet, Ecker turned on his cameras, which shot roughly four frames a second, or one frame for every 70 yards he traveled. Banking away from the site, the pilots returned to Florida, landing at the naval air station in Jacksonville. The film was flown to Andrews Air Force Base outside Washington, D.C. and driven by armed CIA couriers to the National Photographic Interpretation Center, a secret facility occupying an upper floor of a Ford dealership in a derelict block at Fifth and K streets in Northwest Washington. Half a dozen analysts pored over some 3,000 feet of newly developed film overnight.

At 10 o’clock the following morning, CIA analyst Art Lundahl showed Kennedy stunningly detailed photographs that would make it crystal clear that Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev had broken his promise not to deploy offensive weapons in Cuba. As the Cuban missile crisis reached its peak over the next few days, low-flying Navy and Air Force pilots conducted more than 100 missions over the island in Operation Blue Moon. While Kennedy and Khrushchev engaged in a war of nerves that brought the world the closest it has ever come to a nuclear exchange, the president knew little about his counterpart’s intentions—messages between Moscow and Washington could take half a day to deliver. The Blue Moon pictures provided the most timely and authoritative intelligence on Soviet military capabilities in Cuba, during and immediately after the crisis. They showed that the missiles were not yet ready to fire, making Kennedy confident that he still had time to negotiate with Khrushchev.

In the 50 years since the standoff, the U.S. government has published only a handful of low-altitude photographs of Soviet missile sites—a small fraction of the period’s total intelligence haul.